December 16, 2025

Lower survival rates in Black leukemia patients treated with intensive chemotherapy not linked to differences in genetic profiles

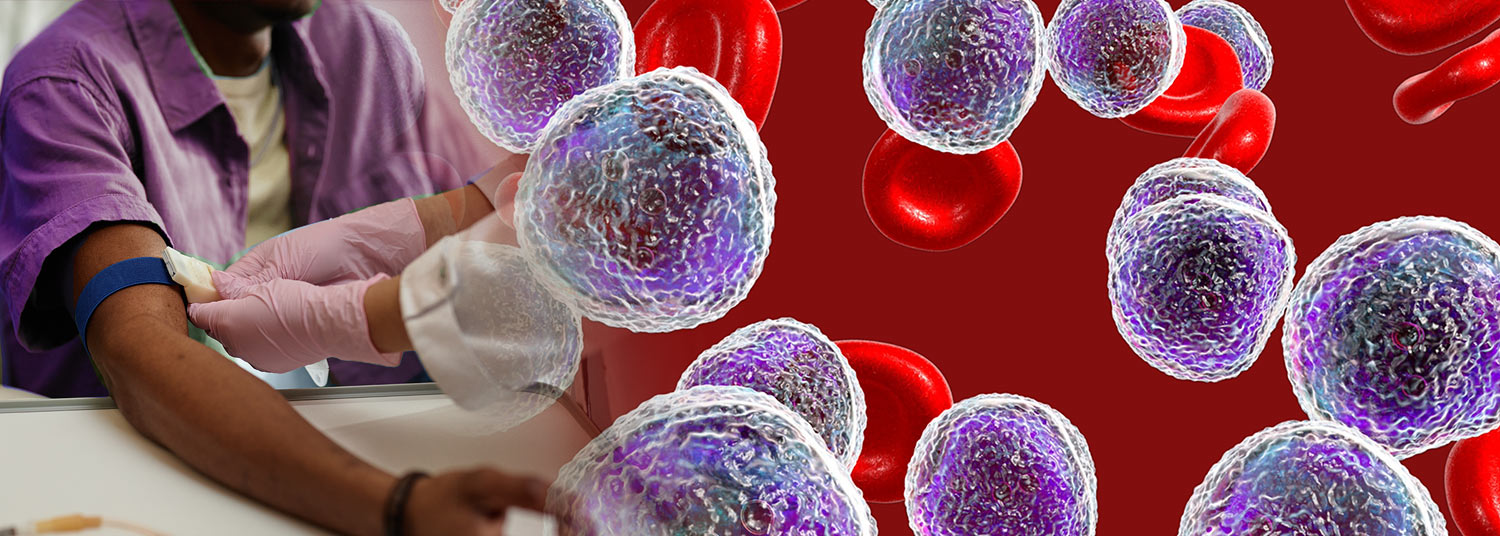

Compared with white patients, Black patients with an aggressive form of leukemia--called acute myeloid leukemia (AML)--were on average more than five years younger at diagnosis and more than 30 percent more likely to die of their disease; that is according to a new analysis of data led by University of Maryland School of Medicine researchers. The study, supported by the National Cancer Institute (NCI), also found that Black patients were more than 20 percent more likely to die of any cause over the 34-year study period. Among patients with a mutation in their cancer cells that is generally associated with more favorable outcomes from treatment, survival for Black patients was less than half that of white patients.

“To our knowledge, this study includes data for a larger number of Black patients than any other such study of AML survival across NCI-supported clinical trials,” said study first author Shella Saint Fleur-Lominy, MD, PhD, an Associate Professor of Medicine at the University of Maryland School of Medicine and a member of the cancer therapeutics program at the University of Maryland Marlene and Stewart Greenebaum Comprehensive Cancer Center. “Our findings confirm those of previous, smaller studies: Black patients with AML develop the disease at a significantly younger age, on average, than white patients and, even when they're treated in clinical trials, they have significantly worse outcomes than white patients.”

Dr. Saint Fleur-Lominy presented the study findings at the annual meeting of the American Society of Hematology earlier this month.

AML is a rare, fast-growing cancer that starts in the bone marrow, the soft tissue inside bones where blood cells form. Early blood-forming cells change (mutate) and begin to grow out of control, resulting in large numbers of abnormal, immature blood cells that spill into the bloodstream and crowd out healthy cells. As a result, AML can cause organs to stop working properly and make the body very sick. Doctors base treatment recommendations on biopsy tests that identify the “profile” of mutations in a patient’s AML cells because different drugs can target different mutations, leading to better responses to treatment and longer survival.

Years of published reports have shown poorer outcomes for Black patients treated for AML compared with white patients, according to Dr. Saint Fleur-Lominy, though the reasons for this disparity are not completely understood. In one recent study, Black patients diagnosed in their teens or under age 40 had worse outcomes than their white counterparts even when they had mutations that, in white patients, are usually associated with more favorable treatment outcomes.

Clinical trials often allow patients with cancer to access novel therapies for their disease before they become widely available. After decades of efforts to promote access to clinical trials for patients of all backgrounds, a 2020 report showed an increase in the number of Black patients in trials supported by the NCI. A related study found a higher rate of Black patients in NCI-sponsored trials than in pharmaceutical company trials. Still, Black patients remain underrepresented in many clinical trials, Dr. Saint Fleur-Lominy said.

In this study, she and her colleagues reviewed the medical records of all patients with newly diagnosed AML who were enrolled in 10 ECOG-ACRIN Cancer Research Group clinical trials between 1984 and 2019. (ECOG-ACRIN is a member of the NCI’s National Clinical Trials Network.) The research team then compared white and Black patients’ overall survival, how long they remained cancer-free after treatment, and differences in genetic mutations found in their cancer cells.

They collected data for a total of 3,469 white patients, 184 Black patients, and 156 patients of other races and ethnicities. Across the 10 trials, the proportion of Black patients enrolled ranged from around 1 percent to 11 percent. The median age of Black patients at AML diagnosis was 47.9 years, compared with 53.5 years for white patients, a statistically significant difference. Moreover, compared with white patients, Black patients had a 31.3 percent higher risk of dying from AML and 21.2 percent higher risk of dying from any cause.

They collected data for a total of 3,469 white patients, 184 Black patients, and 156 patients of other races and ethnicities. Across the 10 trials, the proportion of Black patients enrolled ranged from around 1 percent to 11 percent. The median age of Black patients at AML diagnosis was 47.9 years, compared with 53.5 years for white patients, a statistically significant difference. Moreover, compared with white patients, Black patients had a 31.3 percent higher risk of dying from AML and 21.2 percent higher risk of dying from any cause.

Results showed that the most common mutations seen in AML cells occurred at similar rates in Black and white patients. However, among patients with a mutation in one particular gene, known as NPM1, the analysis found a significant difference in overall survival, with Black patients surviving for a median of 8.9 months compared with 19.1 months for white patients.

“Although the NPM1 mutation is typically associated with more favorable outcomes of AML treatment, we did not see those more favorable outcomes in Black patients,” said Dr. Saint Fleur-Lominy.

While similar numbers of Black and white patients overall received transplants of blood-forming stem cells, only 37 percent of Black patients received stem cells from a healthy, compatible donor compared to nearly 49 percent of white patients. This type of transplant offers patients with high-risk AML the best chance of a cure, Dr. Saint Fleur-Lominy said. The alternative, collecting the patient’s own stem cells and reinfusing them after high-dose chemotherapy, is no longer considered a standard treatment for AML in the United States, she added.

A limitation of the study, she said, is that data on patients’ mutations profiles are less comprehensive than she and her team would have liked. The study includes data for patients treated across four decades, she said, and the advanced technology now available to perform such testing did not exist when clinical trials of AML treatment were conducted in earlier decades.

As a next step, Dr. Saint Fleur-Lominy said that she would like to see the data from this study combined with other data sets of patients with AML to increase the number of patients with comprehensive genetic data and confirm whether the association of certain genetic mutations with AML outcomes differs in Black patients compared with white patients.

This study was conducted by the ECOG-ACRIN Cancer Research Group and funded by the NCI.

Contact

Office of Public Affairs

655 West Baltimore Street

Bressler Research Building 14-002

Baltimore, Maryland 21201-1559

Contact Media Relations

(410) 706-5260

Related stories

Thursday, June 07, 2018

Most Early-Stage Breast Cancer Patients with Intermediate Risk of Recurrence can Safely Avoid Chemotherapy

The majority of women with early-stage estrogen receptor (ER)-positive breast cancer, considered at intermediate risk of having their cancer recur based on a 21-gene test, can safely forgo treatment with chemotherapy, according to a large multicenter clinical study published in the New England Journal of Medicine.