August 31, 2021 | Vanessa McMains

New UM School of Medicine study suggests pre-determined social preference may have implications for interactions ranging from relationship compatibility to understanding diseases associated with social avoidance

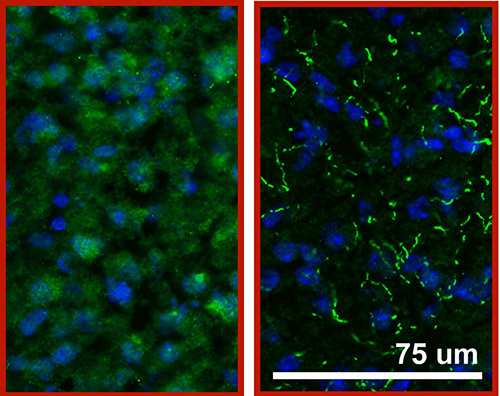

Mouse friends, Credit: Michy Kelly

Have you ever met someone you instantly liked, or at other times, someone who you knew immediately that you did not want to be friends with, although you did not know why?

Popular author Malcolm Gladwell examined this phenomenon in his best-selling book, Blink. In his book, he noted that an “unconscious” part of the brain enables us to process information spontaneously, when, for example, meeting someone for the first time, interviewing someone for a job, or faced with making a decision quickly under stress.

Now, a new study from the University of Maryland School of Medicine (UMSOM) suggests that there may be a biological basis behind this instantaneous compatibility reaction. A team of researchers showed that variations of an enzyme found in a part of the brain that regulates mood and motivation seems to control which mice want to socially interact with other mice — with the genetically similar mice preferring each other.

The UMSOM researchers, led by Michy Kelly, PhD, Associate Professor of Anatomy and Neurobiology, say their findings may indicate that similar factors could contribute to the social choices people make. Understanding what factors drive these social preferences may help us to better recognize what goes awry in diseases associated with social withdrawal, such as schizophrenia or autism, so that better therapies can be developed.

The UMSOM researchers, led by Michy Kelly, PhD, Associate Professor of Anatomy and Neurobiology, say their findings may indicate that similar factors could contribute to the social choices people make. Understanding what factors drive these social preferences may help us to better recognize what goes awry in diseases associated with social withdrawal, such as schizophrenia or autism, so that better therapies can be developed.

The study was published on July 28 in Molecular Psychiatry, a Nature publication.

“We imagine that this is only the first among many biomarkers of compatibility in the brain that may control social preferences,” said Dr. Kelly. “Imagine the possibilities of truly understanding the factors behind human compatibility. You could better match relationships to reduce heartache and divorce rates, or better match patients and doctors to advance the quality of healthcare, as studies have shown compatibility can improve health outcomes.”

A succession of unlikely events and circumstances over the years eventually culminated in this research project, according to Dr. Kelly.

While she was working at a pharmaceutical company, a group of bone researchers asked Dr. Kelly to characterize the behavior of one of their mutant mice that was missing the PDE11 protein. She observed that these mice without PDE11 withdrew socially, so she knew that PDE11 had to be in the brain. She remembered a study that used a mouse model of schizophrenia in which the researchers damaged the brain’s hippocampus leading to antisocial behavior. She then looked at this part of the brain in healthy mice and found where the PDE11 protein was hiding.

Later, as a faculty member at University of South Carolina, she continued studying the social behavior of mutant mice in terms of their social reactions to scent. In the lab, researchers took wooden beads rubbed all over with pungent, airborne pheromones from one group of mice, and placed them in an enclosure with a second group. A mouse presented with one bead from a familiar friend and another from a new stranger mouse would typically spend more time investigating the bead with the stranger’s scent on it. When researchers looked at the PDE11 mutant’s preferences, they favored the stranger’s scent one hour or one week after meeting their friend, but one day after meeting—considered recent long-term memory for a mouse— their social memory seemed fuzzy, and they did not differentiate between a friend and a stranger. To the researchers this meant, the mice’s short and long-term social memory worked fine, but there was a problem coding the information into recent long-term memory—the time between short and long-term memory. Given more time, they would eventually recover that memory.

Later, as a faculty member at University of South Carolina, she continued studying the social behavior of mutant mice in terms of their social reactions to scent. In the lab, researchers took wooden beads rubbed all over with pungent, airborne pheromones from one group of mice, and placed them in an enclosure with a second group. A mouse presented with one bead from a familiar friend and another from a new stranger mouse would typically spend more time investigating the bead with the stranger’s scent on it. When researchers looked at the PDE11 mutant’s preferences, they favored the stranger’s scent one hour or one week after meeting their friend, but one day after meeting—considered recent long-term memory for a mouse— their social memory seemed fuzzy, and they did not differentiate between a friend and a stranger. To the researchers this meant, the mice’s short and long-term social memory worked fine, but there was a problem coding the information into recent long-term memory—the time between short and long-term memory. Given more time, they would eventually recover that memory.

A student working in the laboratory offhandedly remarked that he noticed children with autism prefer to interact with others that have autism. So, Dr. Kelly decided they should test to see if the PDE11 mutants and normal mice had a preference with whom they interacted. The researchers found that PDE11 mutants preferred being around other PDE11 mutants over the normal mice, while normal mice also preferred their own genetic type. This discovery held true even when researchers tested other laboratory mouse strains. When they tested another genetic variant of PDE11 with a single change in the DNA code, mice with that genetic variation preferred other mice with the same variant over any others.

“So, what is it that the mice are sensing that determines their friend preferences?” said Dr. Kelly. “We eliminated smell and body movements as contributing factors, but we still have some other ideas to test.”

“What this team has done is to establish a paradigm by which researchers can identify the social underpinnings of friendship in animal models,” said E. Albert Reece, MD, PhD, MBA, Executive Vice President for Medical Affairs, UM Baltimore, and the John Z. and Akiko K. Bowers Distinguished Professor and Dean, University of Maryland School of Medicine. "This very important finding is just the start, but hopefully will lead to exciting new avenues of biological or social treatments for diseases like schizophrenia or age-related cognitive decline in which severe social avoidance and isolation can reduce a person’s quality of life.”

This study was supported by start-up funds from the University of Maryland School of Medicine, a grant from the National Institute of Mental Health (R01MH101130), and a grant from the National Institute of Aging (R01AG061200).

About the University of Maryland School of Medicine

Now in its third century, the University of Maryland School of Medicine was chartered in 1807 as the first public medical school in the United States. It continues today as one of the fastest growing, top-tier biomedical research enterprises in the world -- with 46 academic departments, centers, institutes, and programs, and a faculty of more than 3,000 physicians, scientists, and allied health professionals, including members of the National Academy of Medicine and the National Academy of Sciences, and a distinguished two-time winner of the Albert E. Lasker Award in Medical Research. With an operating budget of more than $1.2 billion, the School of Medicine works closely in partnership with the University of Maryland Medical Center and Medical System to provide research-intensive, academic and clinically based care for nearly 2 million patients each year. The School of Medicine has nearly $600 million in extramural funding, with most of its academic departments highly ranked among all medical schools in the nation in research funding. As one of the seven professional schools that make up the University of Maryland, Baltimore campus, the School of Medicine has a total population of nearly 9,000 faculty and staff, including 2,500 students, trainees, residents, and fellows. The combined School of Medicine and Medical System (“University of Maryland Medicine”) has an annual budget of over $6 billion and an economic impact of nearly $20 billion on the state and local community. The School of Medicine, which ranks as the 8th highest among public medical schools in research productivity (according to the Association of American Medical Colleges profile) is an innovator in translational medicine, with 606 active patents and 52 start-up companies. In the latest U.S. News & World Report ranking of the Best Medical Schools, published in 2021, the UM School of Medicine is ranked #9 among the 92 public medical schools in the U.S., and in the top 15 percent (#27) of all 192 public and private U.S. medical schools. The School of Medicine works locally, nationally, and globally, with research and treatment facilities in 36 countries around the world. Visit medschool.umaryland.edu

Contact

Vanessa McMains

Director, Media & Public Affairs

University of Maryland School of Medicine

Institute of Human Virology

vmcmains@ihv.umaryland.edu

Cell: 443-875-6099

Related stories

Thursday, September 08, 2022

How Memory of Personal Interactions Declines with Age

One of the most upsetting aspects of age-related memory decline is not being able to remember the face that accompanies the name of a person you just talked with hours earlier. While researchers don’t understand why this dysfunction occurs, a new study conducted at University of Maryland School of Medicine (UMSOM) has provided some important new clues. The study was published on September 8 in Aging Cell.

Tuesday, August 31, 2021

Award-Winning Educator Adam Puche, PhD, Named Vice Chair of Department of Anatomy and Neurobiology

Asaf Keller, PhD, Professor and Chair of Anatomy and Neurobiology at the University of Maryland School of Medicine (UMSOM), along with UMSOM Dean E. Albert Reece, MD, PhD, MBA, announced that award-winning educator Adam Puche, PhD, Professor of Anatomy and Neurobiology, has been appointed to serve as the inaugural Vice Chair of that department, effective immediately.

Wednesday, November 21, 2018

UMSOM Expert Discovers Key Gene in Cells Associated with Age-Related Hearing Loss

An international group of researchers, led by Ronna Hertzano, MD, PhD, Associate Professor, Department of Otorhinolaryngology-Head & Neck Surgery, Anatomy and Neurobiology, at the University of Maryland School of Medicine (UMSOM), and Michael Bowl, Ph.D., Programme Leader Track Scientist, Mammalian Genetics Unit, MRC Harwell Institute, UK, have identified the gene that acts as a key regulator for special cells needed in hearing.